Monday, May 30th, 2016

By Gene Sanders – Guest Author

Manager – W. E. Train Consulting

Tampa, Florida

When is an oxidizer not an Oxidizer?

HazMat (DG, Dangerous Goods) can be such a dry topic that a little bit of humor can really help get us all, students and instructor, through multi-day classes. Another of my attempts at humor, one that hasn’t yet been thrown back at me in an evaluation, is to ask what language our transport regulations are written in. Sure, the words appear in English dictionaries (I’ve not gotten the courage up to deliver a class in Spanish, yet), but when attempting to read the regulations it sometimes appears to be a different language. I ask if Legalese or Regulatory Speak are official languages, and if I’m lucky get rewarded with a few smiles and nods. Everyone seems to understand the concept that whatever the words are, they aren’t clear language. And from there, we’re emotionally prepared whenever we have to go through the arduous task of breaking down and analyzing any particular regulation in order to understand what’s required of us.

HazMat (DG, Dangerous Goods) can be such a dry topic that a little bit of humor can really help get us all, students and instructor, through multi-day classes. Another of my attempts at humor, one that hasn’t yet been thrown back at me in an evaluation, is to ask what language our transport regulations are written in. Sure, the words appear in English dictionaries (I’ve not gotten the courage up to deliver a class in Spanish, yet), but when attempting to read the regulations it sometimes appears to be a different language. I ask if Legalese or Regulatory Speak are official languages, and if I’m lucky get rewarded with a few smiles and nods. Everyone seems to understand the concept that whatever the words are, they aren’t clear language. And from there, we’re emotionally prepared whenever we have to go through the arduous task of breaking down and analyzing any particular regulation in order to understand what’s required of us.

So, to re-ask my original question, when is an oxidizer not an Oxidizer?

Many people think that transport classifications are based upon the intrinsic properties of whatever it is they want to ship. And in most situations these people are right. A drop of gasoline has the same assigned hazards as a truck trailer full of gasoline. The flash point and boiling point are unchanged, and while the drop of gasoline may qualify for some packaging or hazard communication relief, that relief is predicated on knowing the hazard class and packing group (PG) of the drop, which turn out to be the same 3 and II as the full tanker. But not all classifications work this way.

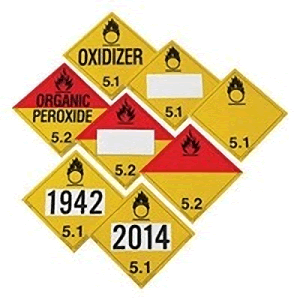

Take, for instance, Division 5.1. When you read the definition of 5.1, and look over the test requirements for assignment of materials to 5.1, you’ll think 5.1 materials are a lot like the gasoline example, and always are 5.1 because they have oxidizing properties. No matter how many times you re-read those 5.1 regulatory passages you can come to the same conclusion. ‘Here’s how you test solids, here’s how you test liquids…,’, wait, what’s going on? There’s no mention of gases in the 5.1 definition (at least not in the 49CFR). But we know some gases do cause or enhance combustion, especially oxygen, and we do know oxygen must be transported as an oxidizer, don’t we?

Well, here’s where it gets interesting.

Pure Oxygen isn’t always a HazMat (Dangerous Good)! For Oxygen, as for Nitrous Oxide, and for any other 2.2 (5.1) gas, it isn’t just the intrinsic properties that determine the transport classification, it a combination of multiple factors, including the intrinsic properties. And while quantity is one of those other factors, it also isn’t the only other factor. A large quantity of pure Oxygen in a large container might not be HazMat, while a smaller quantity of pure Oxygen in an even smaller container might be. This may seem strange at first, but it’s not. It’s the combination of quantity and container size which yields the pressure of the gas, a crucial factor in determining whether some gases are 5.1 oxidizers or not. According to the Class 2 definitions, in order for a gas to be 5.1, it must first be 2.2, and in order to be 2.2, it must be pressurized. If a gas isn’t 2.2, then the test for 5.1 isn’t applicable. So, although the intrinsic properties of Oxygen don’t change, sometimes it gets shipped as HazMat, and thus 5.1, while at other times, depending upon the quantity and container size, it can be legally shipped as stuff, non-haz stuff; non-oxidizing stuff. Who knew?

Classifying, accurately, for transport, isn’t always as easy and simple as some people think it is. There’re reasons why Fisher Scientific tacked on an extra day-and-a-half of advanced transport classification training after getting DGAC to deliver their 2 ½ day basic classification course.

One of those reasons was that oxidizers aren’t always 5.1.

© 2016 W.E. TRAIN CONSULTING ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

P.O. Box 8149

P.O. Box 8149